Optimal Dna Shotgun Sequencing: Noisy Reads Are as Good as Noiseless Reads

- Proceedings

- Open Access

- Published:

Near-optimal assembly for shotgun sequencing with noisy reads

BMC Bioinformatics volume 15, Article number:S4 (2014) Cite this article

Abstruse

Recent work identified the central limits on the information requirements in terms of read length and coverage depth required for successful de novo genome reconstruction from shotgun sequencing data, based on the idealistic assumption of no errors in the reads (noiseless reads). In this work, we testify that fifty-fifty when there is noise in the reads, one tin can successfully reconstruct with data requirements close to the noiseless primal limit. A new associates algorithm, Ten-phased Multibridging, is designed based on a probabilistic model of the genome. It is shown through analysis to perform well on the model, and through simulations to perform well on existent genomes.

Background

Optimality in the conquering and processing of DNA sequence data represents a serious engineering challenge from diverse perspectives including sample preparation, instrumentation and algorithm evolution. Despite scientific achievements such every bit the sequencing of the human genome and ambitious plans for the time to come [1, 2], there is no single, overarching framework to identify the primal limits in terms of information requirements required for successful output of the genome from the sequence data.

Data theory has been successful in providing the foundation for such a framework in digital advice [three], and we believe that it tin can as well provide insights into agreement the essential aspects of Dna sequencing. A first footstep in this direction has been taken in the recent work [iv], where the central limits on the minimum read length and coverage depth required for successful associates are identified in terms of the statistics of various repeat patterns in the genome. Successful assembly is defined as the reconstruction of the underlying genome, i.e. genome finishing [5]. The genome finishing problem is particularly attractive for analysis because it is clearly and unambiguously defined and is arguably the ultimate goal in assembly. At that place is also a scientific demand for finished genomes [vi, vii]. Until recently, automated genome finishing was beyond accomplish [viii] in all just the simplest of genomes. New advances using ultra-long read single-molecule sequencing, all the same, have reported successful automatic finishing [9, 10]. Even in the case where finished assembly is not possible, the results in [4] provide insights on optimal use of read information since the heart of the trouble lies in how one can optimally utilize the read information to resolve repeats.

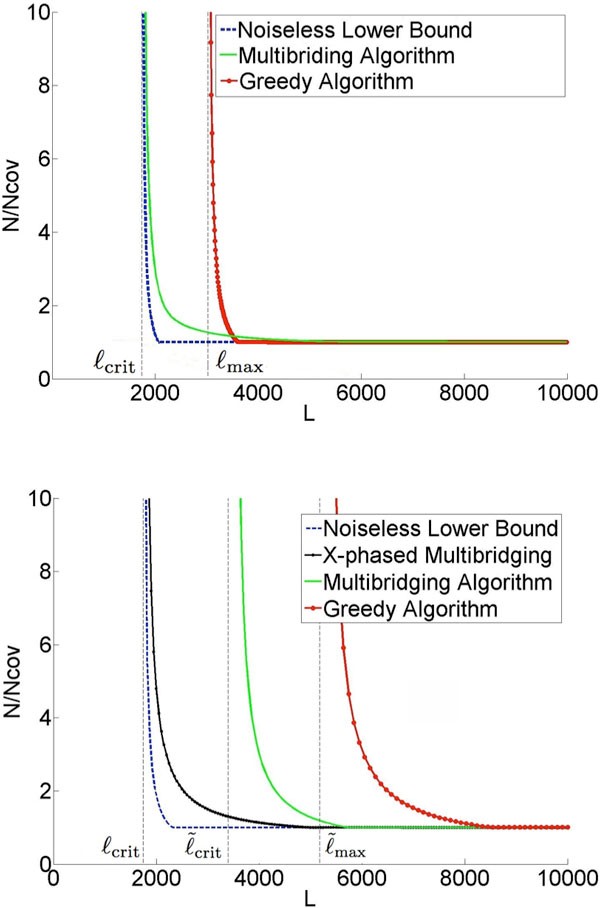

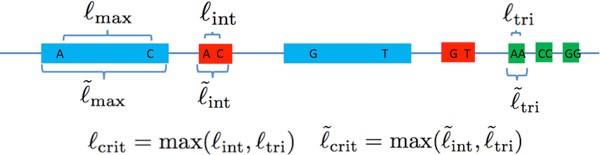

Effigy 1a gives an example result for the repeat statistics of E. coli K12. The x-axis of the

Information requirement to reconstruct East. coli K12. ℓcrit = 1744,

plot is the read length and the y-axis is the coverage depth normalized past the Lander-Waterman depth (number of reads needed to cover the genome [11]). The lower spring identifies the necessary read length and coverage depth required for any assembly algorithm to be successful with these repeat statistics. An assembly algorithm called Multibridging Algorithm was presented, whose read length and coverage depth requirements are very shut to the lower spring, thus tightly characterizing the fundamental information requirements. The result shows a disquisitional phenomenon at a certain read length L =ℓcrit: beneath this critical read length, reconstruction is impossible no matter how high the coverage depth; slightly above this read length, reconstruction is possible with Lander-Waterman coverage depth. This critical read length is given byℓcrit = max{ℓint,ℓtri}, whereℓint is the length of the longest pair of exact interleaved repeats andℓtri is the length of the longest exact triple repeat in the genome, and has its roots in earlier work by Ukkonen on Sequencing-by-Hybridization [12]. The framework also allows the assay of specific algorithms and the comparing with the fundamental limit; the plot shows for example the performance of the Greedy Algorithm and nosotros see that its information requirement is far from the fundamental limit.

A key simplifying supposition in [four] is that there are no errors in the reads (noiseless reads). Yet reads are noisy in all present-day sequencing technologies, ranging from primarily substitution errors in Illumina ® platforms, to primarily insertion-deletion errors in Ion Torren ® and PacBio ® platforms. The following question is the focus of the current paper: in the presence of read noise, can we nonetheless successfully assemble with a read length and coverage depth close to the minimum in the noiseless case? A contempo work [13] with an existing assembler suggests that the data requirement for genome finishing substantially exceeds the noiseless limit. However, it is not obvious whether the limitations prevarication in the fundamental effect of read noise or in the sub-optimality of the algorithms in the assembly pipeline.

Results

The difficulty of the assembly problem depends crucially on the genome repeat statistics. Our approach to answering the question of the fundamental result of read noise is based on design and analysis using a parametric probabilistic model of the genome that matches the key features of the echo statistics we observe in genomes. In particular, it models the presence of long flanked repeats which are repeats flanked past statistically uncorrelated region. Figure 1b shows a plot of the predicted information requirement for reliable reconstruction by diverse algorithms under a substitution mistake rate of 1%. The plot is based on analytical formulas derived nether our genome model with parameters set to match the statistics of E. coli K12. We testify that it is possible in many cases to develop algorithms that approach the noiseless lower leap even when the reads are noisy. Specifically, the X-phased Multibridging Algorithm has close to the aforementioned critical read length L =ℓcrit equally in the noiseless case and only slightly greater coverage depth requirement for read lengths greater than the disquisitional read length.

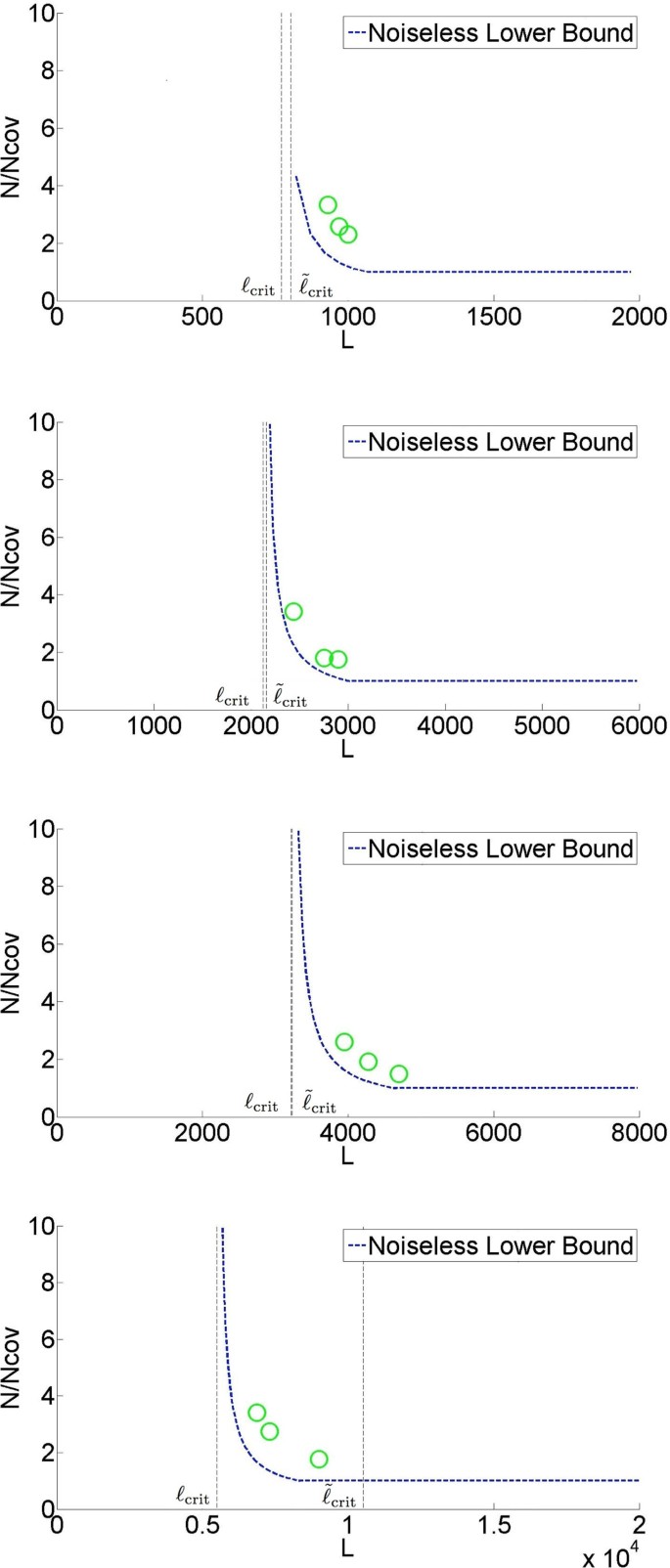

We then go on to build a prototype assembler based on the analytical insights and we perform experiments on real genomes. As shown in Effigy ii, we test the prototype assembler by using it to get together noisy reads sampled from four dissimilar genomes. At coverage and read length indicated past a green circle, nosotros successfully assemble noisy reads into i contig (in most cases with more than 99% of the content matched when compared with the basis truth). Note that the data requirement is close to the noiseless lower bound. Moreover, the algorithm (10-phased Multibridging) is computationally effisscient with the well-nigh computational expensive footstep being the ciphering of overlap of reads/K-mers, which is an unavoidable procedure in almost associates algorithms.

Simulation results on a prototype assembler (substitution noise of rate 1.5 %)

The main decision of this piece of work is that, with an appropriately designed assembly algorithm, the information requirement for genome assembly is surprisingly insensitive to read noise. The basic reason is that the back-up required by the Lander-Waterman coverage constraint can be used to denoise the data. This is consequent with the asymptotic result obtained in [fourteen] and the practical approach taken in [nine]. However, the effect in [14] is based on a very simplistic i.i.d. random genome model, while the model and genomes considered in the nowadays paper both have long repeats. A natural extension of the Multibridging Algorithm in [4] to handle noisy reads allows the resolution of these long flanked repeats if the reads are long enough to span them, thus allowing reconstruction provided that the read length is greater than , where is the length of the longest pair of flanked interleaved repeats andℓtri is the length of the longest flanked triple echo in the genome. This condition is shown as a vertical asymptote of the "Multibridging Algorithm" curve in Figure 1b. By exploiting the redundancy in the read coverage to resolve read errors, the X-phased Multibridging can phase the polymorphism across the flanked repeat copies using just reads that span the exact repeats. Hence, reconstruction is achievable with a read length

close to 50 =ℓcrit,south which is the noiseless limit.

Related work

All assemblers must somehow address the problem of resolving racket in the reads during genome reconstruction. However, the traditional approaches to measuring assembly performance makes quantitative comparisons challenging for unfinished genomes [15]. In most cases, the middle of the assembly problem lies in processing of the associates graph, as in [16–eighteen]. A common strategy for dealing with ambiguity from the reads lies in filtering the massively parallel sequencing data using the graph structure prior to traversing possible assembly solutions. In the present work, however, we are focused on the often-overlooked goal of optimal data efficiency. Thus, to the extent possible we distinguish between the read error and the mapping ambiguity associated with the shotgun sampling process. The proposed assembler, X-phased Multibridging, adds information to the assembly graph based on a novel analysis of the underlying reads.

Methods

The path towards developing X-phased Multibridging is outlined every bit follows.

1 Setting upward the shotgun sequencing model and trouble conception.

2 Analyzing repeats structure of genome and their human relationship to the information requirement for genome finishing.

3 Developing a parametric probabilistic model that captures the long tail of the repeat statistics.

iv Deriving and analyzing an algorithm that require minimal information requirements for assembly -close to the noiseless lower bound.

five Performing simulation-based experiments on real and constructed genomes to characterize the operation of a prototype assembler for genome finishing.

vi Extending the algorithm to address the problem of indel noise.

Shotgun sequencing model and problem conception

Sequencing model

Let south exist a length 1000 target genome being sequenced with each base in the alphabet gear up Σ = {A, C, Thou, T}. In the shotgun sequencing process, the sequencing instrument samples Due north reads, ,..., of length L and sampled uniformly and independently from s. This unbiased sampling assumption is made for simplicity and is as well supported past the characteristics of single-molecule (east.yard. PacBio ®) data. Each read is a noisy version of the respective length L substring on the genome. The dissonance may consist of base insertions, substitutions or deletions. Our analysis focus on substitution noise first. In a later section, indel noise is addressed. In the substitution noise model, let p be the probability that a base of operations is substituted by some other base of operations, with probability p/ 3 to be whatsoever other base. The errors are causeless to be independent across bases and across reads.

Formulation

Successful reconstruction past an algorithm is defined by the requirement that, with probability at least one - ϵ, the reconstruction is a single contig which is within edit distance δ from the target genome s. If an algorithm tin can achieve that guarantee at some (N, 50), it is called ϵ-viable at (North, L). This conception implies automated genome finishing, because the output of the algorithm is one single contig. The fundamental limit for the assembly trouble is the set of (N, L) for which successful reconstruction is possible by some algorithms. If is directly spelled out from a right placement of the reads, the edit distance between and south is of the order of pG, where the error rate is p. This motivates fixing δ = 2pG for concreteness. The quality of the assembly tin can exist farther improved if we follow the assembly algorithm with a consensus stage in which we correct each base, eastward.g. with majority voting. Only the consensus phase is not the focus in this paper.

Repeats structure and their relationship to the information requirement for successful reconstruction

Long verbal repeats and their relationship to assembly with noiseless reads

Nosotros take a moment to carefully ascertain the various types of exact repeats. Let announce the length-ℓ substring of the Dna sequence southward starting at position t. An exact repeat of length ℓ is a substring appearing twice, at some positions t one, t two (so ) that is maximal (i.e. s(t 1 - 1) ≠ south(t 2 - ane) and s(t 1 +ℓ) ≠ s(t 2 +ℓ)).

Similarly, an verbal triple repeat of length-ℓ is a substring appearing three times, at positions t one, t 2, t 3, such that , and such that neither of due south(t ane - 1) = s(t two - 1) = due south(t 3 - ane) nor s(t 1+ℓ) = s(t 2+ℓ) = s(t 3 +ℓ) holds.

A copy of a repeat is a single ane of the instances of the substring appearances. A pair of exact repeats refers to ii verbal repeats, each having two copies. A pair of verbal repeats, one at positions t i, t 3 with t 1 < t 3 and the second at positions t 2, t iv with t two < t 4, is interleaved if t ane < t 2 < t 3 < t 4 or t 2 < t 1 < t 4 < t 3. The length of a pair of verbal interleaved repeats is de-fined to exist the length of the shorter of the two exact repeats. A typical appearance of a pair of exact interleaved repeat is -X-Y-Ten-Y- where × and Y stand for two dissimilar exact echo copies and the dashes represent non-identical sequence content.

We letℓmax be the length of the longest exact repeat,ℓint be the length of the longest pair of exact interleaved repeats andℓtri be the length of the longest verbal triple repeat.

As mentioned in the introduction, it was observed that the read length and coverage depth required for successful reconstruction using noiseless reads for many genomes is governed by long exact repeats. For some algorithms (e.g. Greedy Algorithm), the read length requirement is bottlenecked byℓmax . The Multi-bridging Algorithm in [iv] tin successfully reconstruct the genome with a minimum amount of information. The corresponding minimum read length requirement is the disquisitional exact repeat lengthℓcrit = max(ℓint,ℓtri).

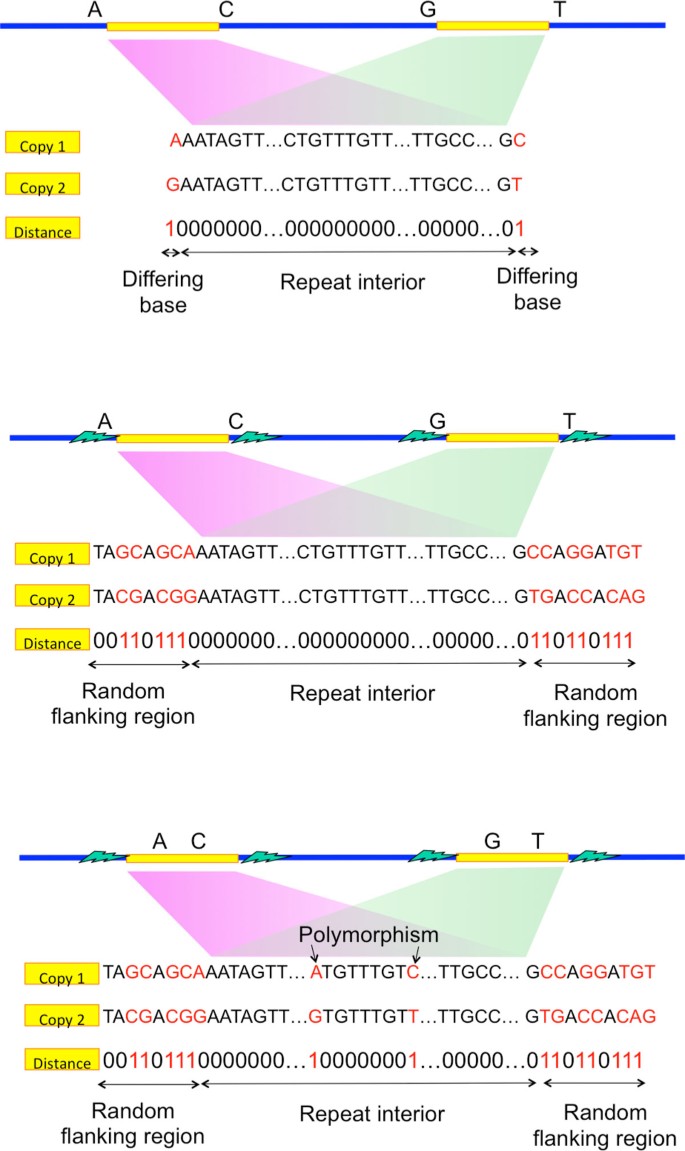

Flanked repeats

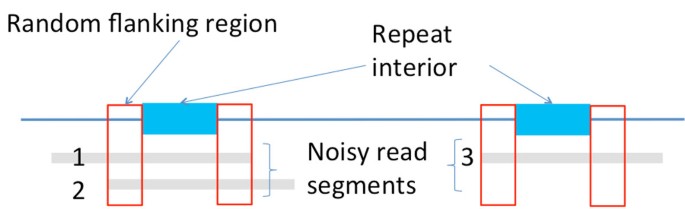

While exact repeats are defined as the segments terminated on each stop by a single differing base (Figure 3a), flanked repeats are defined by the segments terminated on each terminate past a statistically uncorrelated region. We call that ending region to exist the random flanking region. A distinguishing feature of the random flanking region is a loftier Hamming distance to segment length ratio between the ends of two repeat copies. The ratio in the random flanking region is around 0.75, which matches with that when the genomic content is independently and uniformly randomly generated. We observe that long repeats of many genomes end with random flanking region. Additional statistical assay is detailed in the Appendix.

Echo design.

If the repeat interior is exactly the same between two copies of the flanked repeat (Figure 3b), the corresponding flanked repeat is called a flanked exact repeat. If at that place are a few edits (called polymorphism) within the repeat interior (Effigy 3c), the corresponding flanked repeat is called a flanked approximate echo.

The length of the repeat interior bounded by the random flanking region is then the flanked echo length. We let be the length of the longest flanked echo, be the length of the longest pair of flanked interleaved repeats and be the length of the longest flanked triple repeat. The critical flanked repeat length is then .

Long flanked exact repeats and their relationship to assembly with noisy reads

If all long flanked repeats are flanked exact repeats, nosotros can utilize the information in the random flanking region to generalize Greedy Algorithm and Multi-bridging Algorithm to handle noisy reads. The corresponding information requirement is very similar to that when we are dealing with noiseless reads.

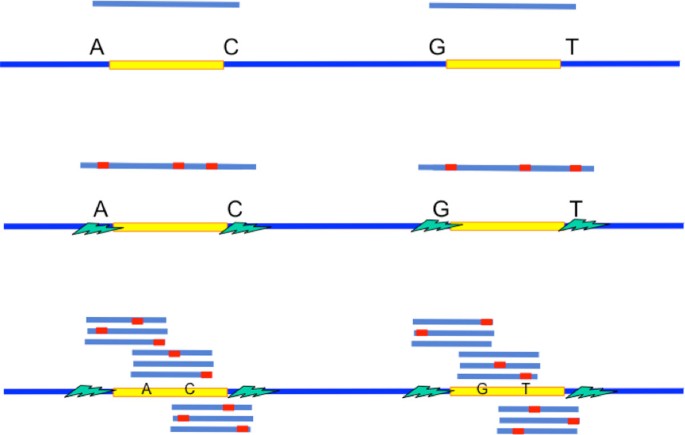

The cardinal intuition is as follows. A criterion for successful reconstruction is the existence of reads to span the repeats to their neighborhood. When a read is noiseless, it only need to be long enough to span the echo interior to its neighborhood by one base (Effigy 4a) so every bit to differentiate between two exact repeat copies. When a read is noisy, it so need to be long enough to bridge the echo interior plus a short extension into the random flanking region (Figure 4b) so as to confidently differentiate betwixt two flanked repeat copies. Withal, the Hamming altitude between ii flanked repeat copies' neighborhood in the random flanking region is very high even inside a brusque length. This can be used to differentiate between two flanked repeat copies confidently even when the reads are noisy. The brusk extension into the random flanking region has a length which is typically of club of tens whereas the long repeat length is of order of thousands. Therefore, relative to the repeat length, the change of the critical read length requirement from handling noiseless reads to noisy reads is only marginal when all long repeats are flanked exact repeats.

Intuition behind the information requirement.

Long flanked approximate repeats and their relationship to associates with noisy reads

If a long flanked repeat is a flanked approximate repeat, the flanked repeat length may exist significantly longer than the length of its longest enclosed exact repeat. Merely relying on the data provided past the random flanking region requires the reads to be of length longer than the flanked repeat length for successful reconstruction. This explains why the information requirement for Greedy Algorithm and Multibridging Algorithm has a significant increment when we use noisy reads instead of noiseless reads (equally shown in Figure 1b). However, if we utilize the information provided past the coverage, we can still confidently differentiate dissimilar repeat copies by phasing the small edits within the repeat interior (Figure 4c). Specifically, we design X-phased Multibridging whose information requirement is close to the noiseless lower bound even when some long repeats are flanked approximate repeats, equally shown in Figure 1b.

From information theoretic insight to algorithm blueprint

Considering of the structure of long flanked repeats, there are two of import sources of data that we specifically want to utilize when designing data efficient algorithms to get together noisy reads. They are

The random flanking region beyond the echo interior

The coverage given by multiple reads overlapping at the same site

Greedy Algorithm(Alg i) utilizes the random flanking region when considering overlap. The minimum read length needed for successful reconstruction is shut to .

Multibridging Algorithm(Alg 2) as well utilizes the random flanking region but it improves upon Greedy Algorithm by using a De Bruijn graph to aid the resolution of flanked repeats. The minimum read length needed for successful reconstruction is close to .

X-phased Multibridging(Alg three) farther utilizes the coverage given past multiple reads to phase the polymorphism within the repeat interior of flanked estimate repeats. The minimum read length needed for successful reconstruction is close toℓcrit, which is the noiseless lower leap even when some long repeats are flanked approximate repeats.

Model for genome

To capture the primal characteristics of repeats and to guide the design of assembly algorithms, we utilise the following parametric probabilistic model for genome. A target genome is modeled as a random vector s of length K that has the following three key components (a pictorial representation is depicted in Figure v).

Model for genome.

Random groundwork: The background of the genome is a random vector, composed of uniformly and independently picked bases from the alphabet prepare Σ= {A, C, G, T}.

Long flanked repeats: On top of the random background, we randomly position the longest flanked repeat and the longest flanked triple repeat. Moreover, nosotros randomly position a flanked repeat interleaving the longest flanked echo, forming the longest pair of flanked interleaved echo. The corresponding length of the flanked repeats are , , and respectively. It is noted that .

Polymorphism and long exact repeats: Within the repeat interior of the flanked repeats, we randomly position north max, due north int and northward tri edits (polymorphism) respectively. The sites of polymorphism are chosen such that the longest exact repeat, the longest pair of exact interleaved repeats and the longest exact triple echo are of lengthℓmax,ℓint andℓtri respectively.

Algorithm design and analysis

Greedy Algorithm

Read R 2 is a successor of read R i if there exists length-West suffix of R 1 and length-West prefix of R 2 such that they are extracted from the same locus on the genome. Furthermore, there is no other reads that tin satisfy the same status with a larger West. To properly determine successors of reads in the presence of long repeats and noise, we need to ascertain an appropriate overlap rule for reads. In this department, we bear witness the conceptual development towards defining such a dominion, which is chosen RA-rule.

Noiseless reads and long verbal repeats: If the reads are noiseless, all reads can exist paired upward with their successors correctly with high probability when the read length exceedsℓmax. It was done [4] by greedily pairing reads and their candidate successors based on their overlap score in descending order. When a read and a candidate successor are paired, they will be removed from the pool for pairing. Here the overlap score betwixt a read and a candidate successor is the maximum length such that the suffix of the read and prefix of the candidate successor match exactly.

Noisy reads and random background: Since we cannot look verbal match for noisy reads, nosotros need a different mode to define the overlap score. Let us consider the following toy state of affairs. Presume that we have exactly one length-(ℓ + 1) noisy read starting at each locus of a length G random genome(i.due east. merely consists of the random background). Each read then overlaps with its successor precisely past ℓ bases. Analogous to the noiseless case, one would expect to pair reads greedily based on overlap score. Here the overlap score between a read and a candidate successor is the maximum length such that the suffix (x) of the read and prefix (y) of the candidate successor friction match approximately. To determine whether they lucifer approximately, one can apply a predefined a threshold factor α and compute the Hamming distance d(x, y). If d(ten, y) ≤ α· ℓ, then they match approximately, otherwise not. Given this conclusion rule, we tin have false positive (i.e. having whatsoever pairs of reads mistakenly paired upward) and false negative (i.e. having any reads non paired upwardly with the true successors). If simulated positive and false negative probability are small, this naive method is a reliable plenty metric. This can be accomplished by using a long plenty length ℓ >ℓiid and an appropriately chosen threshold α.

Recall that ∈is the overall failure probability. By bounding the sum of false positive and false negative probability by ϵ/ 3, one can findℓiid (p, ϵ/ 3, One thousand) and α(p, ϵ/ three, G) to be the (ℓiid, α) solution to the following pair of equations:

(i)

(2)

where is the Kullback-Leibler divergence.

Noisy reads and long flanked repeats: Nevertheless, when the genome contains long flanked repeats on pinnacle of the random background, this naive rule of determining overlap is non enough. Permit us await at the example in Figure 6. As shown in Figure half dozen, because of long flanked repeats, nosotros have a minor ratio of overall distance against the overlap length for the segments that are extracted from different copies of the echo (e.g Segment 1 and Segment 3 in Figure 6). Therefore, the overall Hamming distance between two segments is not a good enough metric for defining overlap. If we abide by the naive rule, we demand to increase the read length significantly longer than the flanked repeat length so equally to guarantee confidence in deciding approximate match. Otherwise, information technology will either result in a high false positive rate (if we set a large α) or a high false negative charge per unit (if nosotros ready a small α). To properly handle such scenario, we ascertain a repeat-aware dominion(or RA-dominion).

Intuition about why we ascertain the overlap rule to exist RA-overlap dominion.

· RA-matching: Two segments (x, y) of length W match under the RA-rule if and only if the distance between whole segments is < α · Due west and both of its ending segments(of length ℓiid) too have distance < α · ℓ iid.

· RA-overlap: The overlap score betwixt a read and a candidate successor under the RA-rule is the maximum length such that the suffix of the read and prefix of the candidate successor match under the RA-matching.

The RA-rule is particularly useful because it puts an accent on both ends of the overlap region. Since the ends are separated by a long range, 1 terminate will hopefully originate from the random flanking region of the flanked repeat. If we focus on the segments originating from the random flanking region, the altitude per segment length ratio will be very high when the segments originate from dissimilar copies of the repeat but very low when they originate from the same copy of the repeat. This is how we utilise the random flank-ing region to differentiate betwixt repeat copies and determine correct successors in the presence of long flanked repeats and dissonance.

If we utilize Greedy Algorithm (Alg one) to merge reads greedily with this overlap rule (RA-dominion), Prop 1 shows the information requirement under the previously described sequencing model and genome model. A plot is shown in Effigy 1b. Sinceℓiid is of order of tens whereas is of order of thousands, the read length requirement for Greedy Algorithm to succeed is dominated by . The detailed proof of Prop 1 is given in Appendix.

Algorithm ane Greedy Algorithm

Initialize contigs to be reads

for W = 50 to ℓ iid do

if any ii contigs x, y are of overlap W under RA-rule

so

merge x, y into one contig.

end

cease

Proffer 1 With , if

then, Greedy Algorithm(Alg ane) is ϵ - feasible at (N, L).

Multibridging Algorithm

The read length requirement of Greedy Algorithm has a bottleneck around considering it requires at least one copy of each flanked repeat to be spanned by at least one read for successful reconstruction. Spanning a repeat past a single read is called bridging in [4]. A natural question is whether we need to have all repeats bridged for successful reconstruction.

In the noiseless setting, [4] shows that this status can be relaxed. Using noiseless reads, i can have successful reconstruction given all copies of each verbal triple repeat being bridged, and at least ane copy of 1 of the repeats in each pair of verbal interleaved repeats being bridged.

A cardinal idea to allow such a relaxation in [4] is to apply a De Bruijn graph to capture the construction of the genome.

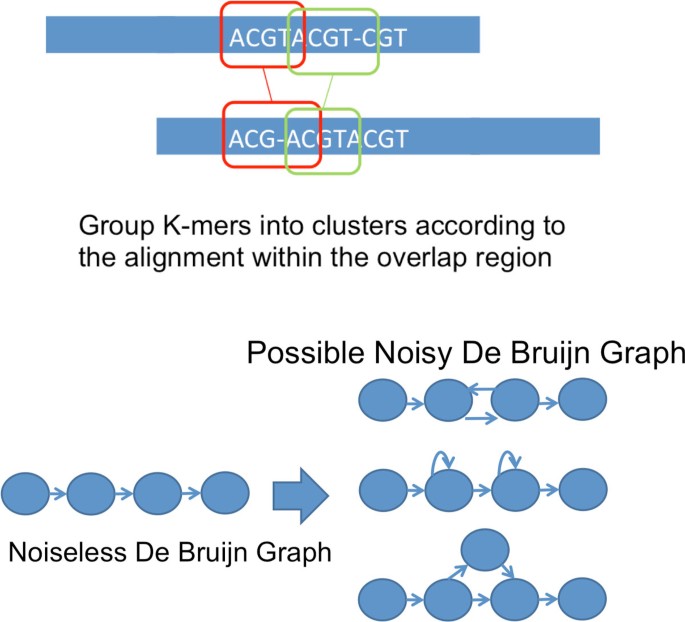

When the reads are noisy, nosotros can utilize the random flanking region to specify a De Bruijn graph with high confidence by RA-rule and arrive at a similar relaxation. Past some graph operations to handle the residue errors, nosotros can have successful reconstruction with read length . The algorithm is summarized in Alg 2. Prop 2 shows its information requirement under the previously described sequencing model and genome model. A plot is shown in Figure 1b. We annotation that Alg 2 tin be seen as a noisy reads generalization of Multibridging Algorithm for noiseless reads in [iv].

Description and its functioning

Proffer 2 With , if

then, Multibridging Algorithm(Alg ii) is ϵ - feasible at (Northward, L).

Detailed proof is given in the Appendix. The following sketch highlights the motivation behind the fundamental steps of Multibridging Algorithm.

[Step1] We ready a large One thousand value to brand sure the K-mers overlapping the shorter repeat of the longest pair of flanked interleaved repeats and the longest flanked triple echo can be separated as singled-out clusters.

[Step2] Clustering is done using the RA-dominion because of the beingness of long flanked repeats and noise.

[Step3] A K-mer cluster corresponds to an equivalence class for K-mers matched under the RA-dominion. This step forms a De Bruijn graph with K-mer clusters as nodes.

[Step4] Because of large Chiliad, the graph can be disconnected due to bereft coverage. In order to reduce the coverage constraint, we connect the clusters greedily.

[Step5, 7] These 2 steps simplify the graph. [Step6] Branch immigration repairs any incorrect merges near the boundary of long flanked repeat.

[Step8] Since an Euler path in the condensed graph corresponds to the correct genome sequence, information technology is traversed to class the reconstructed genome.

Some implementation details: improvement on time and space efficiency

For Multibridging Algorithm, the most computational expensive step is the clustering of Yard-mers. To improve the fourth dimension and infinite efficiency, this clustering pace can be approximated past performing pairwise comparing of reads.

Algorithm two Multibridging Algorithm

1. Cull Thou to be and extract Grand-mers from reads.

2. Cluster K-mers based on the RA-dominion.

3. Form uncondensed De Bruijn graph G De - Bruijn = (V, E) with the following rule:

a) K-mers clusters equally node set V .

b) (u, five) = eastward ϵ E if and only if at that place exists K-mers u 1 ϵ u and v 1 ϵ v such that u 1,v aneare sequent G-mers in some reads.

four. Bring together the disconnected components of G De-Bruijn together past the following rule:

for W = K - 1 to ℓ iid do

for each node u which has either no predecessors / successors in ThouDe-Bruijn do

a) Find the predecessor/successor five for u from all possible Chiliad-mers clusters such that overlap length(using any representative K-mers in that cluster) betwixt u and v is W under RA-rule.

b) Add together dummy nodes in the De Bruijn graph to link u with v and update the graph to G De-Bruijn end

finish

5. Condense the graph G De - Bruijn to course G string with the following rule:

a)Initialize G string to be One thousand De - Bruijn with node labels of each node being its cluster group index.

b)while ∃ successive nodes u → v such that out - caste(u) = 1and in - degree(v) = 1 exercise

bi) Merge u and v to form a new node w

bii) Update the node label of west to exist the concatenation of node labels of u and five

end

- 6.

Articulate Branches of G string :

for each node u in the condensed graph Gcord do

if out - degree(u) > i and that all the successive paths are of the aforementioned length(measured by the number of node labels) and and then joining back to node v and the path length < ℓiid

then

we merge the paths into a single path from u to five.

end

terminate

7. Condense graph G string

8. Find the genome :

a)Notice an Euler Cycle/Path in G string and output the concatenation of the node labels to form a string .

b)Using and look up the associated K-mers to form the final recovered genome .

Based on the alignment of the reads, we tin cluster K-mers from different reads together using a disjoint set up information structure that supports marriage and discover operations. Since merely reads are used in the alignment, only the 1000-mer indices forth with their associated read indices and offsets need to be stored in memory-- not all the K-mers.

Pairwise comparison of reads roughly runs in if washed in the naive way. To speed up the pairwise comparing of noisy reads, one can use the fact that the read length is long. We can excerpt all consecutive f-mers (which act equally fingerprints) of the reads and do a lexicographical sort to find candidate neighboring reads and associated offsets for comparison. Since the reads are long, if ii reads overlap, in that location should be some perfectly matched f-mers which can exist identified after the lexicographical sort. This allows an optimized version of Multibridging Algorithm to run in fourth dimension and space.

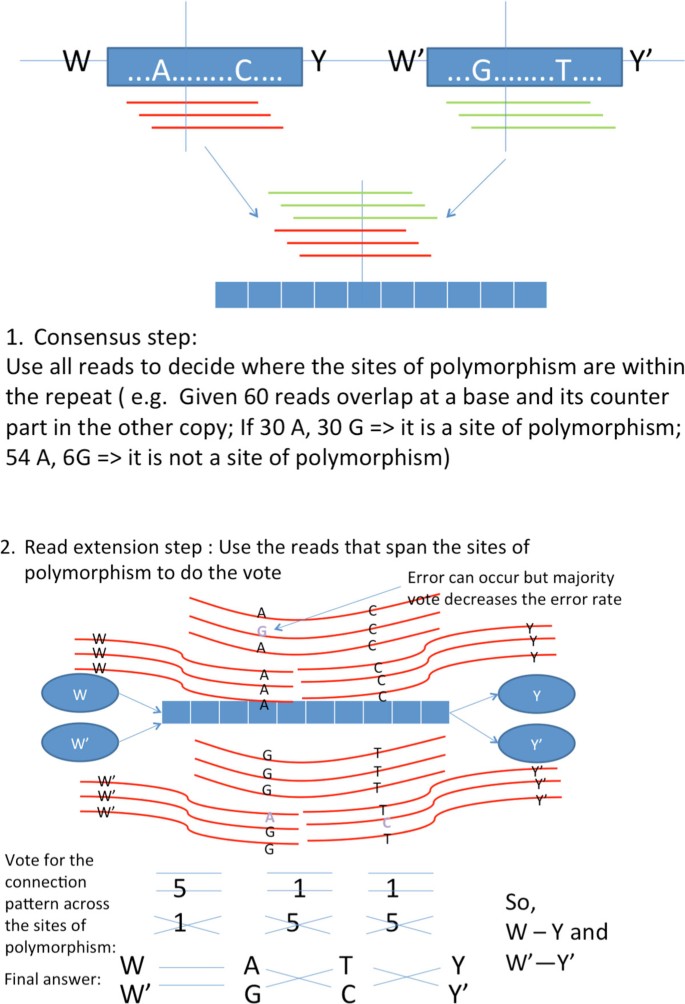

X-phased Multibridging

As shown in Figure 1b, when long repeats are flanked approximate repeats, there can be a big gap between the noiseless lower leap and the information requirement for Multibridging Algorithm. A natural question is whether this is due to a central lack of information from the reads or whether Multibridging Algorithm does not utilize all the available data. In this department, we demonstrate that there is an important source of information provided past coverage which is not utilized past Multibridging Algorithm. In particular, we innovate X-phased Multibridging, an assembly algorithm that utilizes the data provided by coverage to phase the polymorphism in long flanked repeat interior. The information requirement of X-phased Multibridging is shut to the noiseless lower bound (as shown in Effigy 1b) fifty-fifty when some long repeats are flanked gauge repeats.

Clarification of X-phased Multibridging

Multibridging Algorithm utilizes the random flanking region to differentiate between echo copies. However, for a flanked approximate repeat, its enclosed exact repeat does non terminate with the random flanking region but only terminates with sparse polymorphism. When nosotros consider the overlap of two reads originating from different copies of a flanked approximate repeat, the distinguishing polymorphism is so sparse that it cannot be used to confidently differentiate between echo copies. Therefore, in that location is a need to use the extra redundancy introduced by the coverage from multiple reads to confidently differentiate between echo copies and that is what X-phased Multibridging utilizes.

X-phased Multibridging (Alg iii) follows the algorithmic design of Multibridging Algorithm. However, it adds an actress phasing process to differentiate between repeat copies of long flanked repeats that Multi-bridging Algorithm cannot confidently differentiate. We retrieve that after running pace 7 of Multibridging Algorithm, a node in the graph G string corresponds to a substring of the genome and has node label consisting of sequent Grand-mer cluster indices. An 10-node of One thousand string is a node that has in-degree and out-caste ≥ 2. X-node indeed corresponds to a flanked echo. The incoming/outgoing nodes of the X-node correspond to the incoming/approachable random flanking region of the flanked repeat.

To be physical, we focus the word on a pair of flanked interleaved repeats, assuming triple repeats are not the clogging. However, the ideas presented tin be generalized to repeats of more than copies.

For the flanked approximate repeat with length ℓint < Fifty and (as shown in Effigy 7), at that place is no node-disjoint paths joining incoming/outgoing random flanking region with the singled-out echo copies in Thousand cord . It is because the reads are corrupted by noise and the polymorphism is too sparse to differentiate between the echo copies. Executing Multibridging Algorithm directly will result in the formation of an X-node, which is an artifact due to Chiliad-mers from unlike copies of the flanked approximate repeat erroneously clustered together.

Illustration of how to phase polymorphism to extend reads across repeats.

Successful reconstruction requires an algorithm to pair up the correct incoming/outgoing nodes of the X-node(i.e. make up one's mind how and are linked in Figure 7). This is handled by the phasing procedure in Ten-phased Multibridging, which uses all the reads information. The phasing process is composed of ii main steps:

Consensus pace: Confidently observe out where the sites of polymorphism are located inside the flanked repeat interior.

Read extension step: Confidently determine how to extend reads using the random flanking region and sites of polymorphism every bit anchors.

Consensus footstep For the X-node of interest, allow D be the prepare of reads originating from whatever sites of the associated flanked echo region and let 10 i and ten two denote the associated repeat copies. Since the random flanking region is used as anchor, information technology is treated every bit the starting base (i.eastward. ten 1(0) = West and ). For the i thursday subsequent site of the flanked repeat (where ), we decide the consensus co-ordinate to Eq (iii). This can be implemented by counting the frequency of occurrence of each alphabet overlapping at each site of the repeat. The consensus result determines the sites of polymorphism and the most likely pairs of bases at the sites of polymorphism.

(3)

Read extension step After knowing the sites of polymorphism, we utilize those reads that bridge the sites of polymorphism or random flanking region to help decide how to extend reads beyond the flanked repeat. Let σ exist the possible configuration of alphabets at the sites of polymorphism and random flanking region (e.thou. means that the two copies of the flanked repeat with the corresponding random flanking region respectively are Westward-A-C-Y, W'-G-T-Y' where the mutual bases are omitted).

Algorithm 3 X-phased Multibridging

1. Perform Step 1 to Step seven of MultiBridging Algorithm

2. For every X-node x ϵ G string

a)Marshal all the relevant reads to the flanked repeat ten

b)Consensus step: Consensus to find location of polymorphism by solving Eq (3)

c)Read extension step: If possible, resolve flanked repeat(i.e. pair up the incoming/outgoing nodes of x) by either countAlg or by solving Eq (4)

iii. Perform Pace 8 of MultiBridging Algorithm equally in Alg 2

The post-obit maximum a posteriori estimation is used to decide the right configuration.

where is the figurer, D is the raw read set, and ten 1, x 2 are the estimates from the consensus pace. Information technology is noted that the size of the feasible ready for σ is .

In practise, for computational effciency, the maximization in Eq (4) can be approximated accurately even if it is replaced by the simple counting illustrated in Effigy 7, which we call count-to-extend algorithm(countAlg). CountAlg uses the raw reads to establish majority vote on how one should extend to the adjacent sites of polymorphism using but the reads that span the sites of polymorphism.

Performance

After introducing the phasing procedure in X-phased Multibridging, we go along to find its information requirement for successful reconstruction.

The information requirement for X-phased Multibridging is the amount of information required to reduce the fault of the phasing procedure to a negligible level. The phasing procedure - step ii in Alg. iii - is a combination of consensus and read extension steps, which contribute to the mistake as follows.

Permit ε be the error result of the repeat phasing procedure for a repeat, ϵ one be the error probability for the consensus footstep, ϵ 2 exist the mistake probability for the read= extension step given k reads spanning each consecutive site of polymorphism inside the flanked repeat, δ cov be the probability for having k reads spanning each consecutive sites of polymorphism(i.due east. yard bridging reads) within the flanked repeat. We take,

(5)

Therefore, to guarantee confidence in the phasing process, it suffices to upper bound ϵ 1,ϵ 2 and δ cov . We tabulate the fault probabilities of ϵ i, ϵ two in Table 1 for phasing a flanked repeat (whose length is 5000 whereas the genome length is 5M). The flanked echo has two sites of polymorphism which partition information technology into three equally spaced segments.

From Table i, when p = 0.01, the data requirement translates to the status of having three bridging reads spanning the shorter exact echo of the longest pair of exact interleaved repeats. Therefore, the information requirement for X-phased Multibridging shown in Effigy 1b also corresponds to this condition. It is noted that X-phased Multibridging has the same vertical asymptote equally the noiseless lower spring. The vertical shift is due to the increase of requirement on the number of bridging reads from thousand = 1 (noiseless case) to chiliad = 3 (noisy case).

Simulation of the epitome assembler

Based on the algorithmic design presented, we implement a prototype assembler for automated genome finishing using reads corrupted past exchange noise. Kickoff, the assembler was tested on synthetic genomes, which were generated according to the genome model described previously. This demonstrates a proof-of-concept that one can achieve genome finishing with read length close toℓcrit, as shown in Figure 8. The number on the line represents the number of simulation rounds (out of 100) in which the reconstructed genome is a unmarried contig with ≥ 99% of its content matching the ground truth.

Simulation results on the assembly of synthetic genomes using reads corrupted by substitution noise. The parameters are as follows. , , ℓ int = 100 with two sites of polymorphism inside the flanked echo. p = 1.five%, ∈= 5%.

Second, the assembler was tested using synthetic reads, sampled from genome basis truth downloaded from NCBI. The associates results are shown in Table 2. The observation from the simulation upshot is that nosotros can gather genomes to finishing quality with information requirement near the noiseless lower bound. More information about the detail design of the prototype assembler is presented in the Appendix and source code/data set can be found in [xix].

Extension to handle indel noise

A farther extension of the prototype assembler addresses the instance of reads corrupted by indel racket. Like to the case of commutation noise, tests were performed on constructed reads sampled from existent genomes and synthetic genomes. Simulation results are summarized in Table three where p i , p d are insertion probability and deletion probability and charge per unit is the number of successful reconstruction(i.e. simulation rounds that evidence mismatch < five%) divided by total number of simulation rounds. The simulation result for indel noise corrupted reads shows that X-phased Multibridging can be generalized to assemble indel racket corrupted reads. The information requirement for automatic finishing is about a factor of two from the noiseless lower bound for both N and L.

We remark that i non-trivial generalization is the way that we form the noisy De Bruijn graph for K-mer clusters. In particular, nosotros showtime compute the pairwise overlap alignment amid reads, then we use the overlap alignment to group K-mers into clusters. Subsequently, we link successive cluster of K-mers together as we do in Alg 2. An illustration is shown in Effigy 9a. Nevertheless, due to the noise existence indel in nature, the edges in the noisy De Bruijn graph may point in the wrong direction as shown in Effigy 9b. In gild to handle this, we traverse the graph and remove such abnormality when they are detected.

Handling of reads corrupted past indel noise

Determination

In this work, nosotros show that even when at that place is noise in the reads, one tin successfully reconstruct with data requirements close to the noiseless fundamental limit. A new associates algorithm, 10-phased Multi-bridging, is designed based on a probabilistic model of the genome. It is shown through analysis to perform well on the model, and through simulations to perform well on existent genomes.

The chief determination of this work is that, with an appropriately designed assembly algorithm, the information requirement for genome assembly is insensitive to moderate read noise. We believe that the information theoretic insight is useful to guide the design of future assemblers. We hope that these insights let futurity assemblers to meliorate leverage the high throughput sequencing read data to provide college quality associates.

Additional file 1

Details of the proofs, in-depth description of the blueprint of the prototype assembler and details of simulation results are presented.

References

-

Peter Turnbaugh, Ruth Ley, Micah Hamady, Fraser-Liggett Claire, Rob Knight, Jeffrey Gordon: The human being microbiome project. Nature. 2007, 449 (7164): 804-810. 10.1038/nature06244.

-

DNA SEQUENCING: A plan to capture man diverseness in 1000 genomes. Science. 2007, 21: 1842-

-

Claude E Shannon: A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell Arrangement Technical Journal. 1948, 27: 379-423. 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x. 623-656, July, October

-

Guy Bresler, Ma'ayan Bresler, David Tse: Optimal assembly for high throughput shotgun sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013

-

Mihai Popular: Genome assembly reborn:contempo computational challenges. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2009, x (4): 354-366. 10.1093/bib/bbp026.

-

Duccio Medini, Davide Serruto, Julian Parkhill, David Relman, Claudio Donati, Richard Moxon, Stanley Falkow, Rino Rappuoli: Microbiology in the post-genomic era. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008, half-dozen (vi): 419-430.

-

Elaine Mardis, John McPherson, Robert Martienssen, Richard Wilson, McCombie Westward Richard: What is finished, and why does it thing. Genome research. 2002, 12 (5): 669-671. x.1101/gr.032102.

-

David Gordon, Chris Abajian, Phil Light-green: Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome research. 1998, eight (3): 195-202. ten.1101/gr.8.3.195.

-

Chen-Shan Chin, David Alexander, Patrick Marks, Aaron Klammer, James Drake, Cheryl Heiner, Alicia Clum, Alex Copeland, John Huddleston, Evan Eichler: Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read smrt sequencing data. Nature methods. 2013

-

Sergey Koren, Michael Schatz, Brian Walenz, Jeffrey Martin, Jason Howard, Ganeshkumar Ganapathy, Zhong Wang, David Rasko, McCombie Westward Richard, Erich Jarvis: Hybrid fault correction de novo associates of unmarried-molecule sequencing reads. Nature biotechnology. 2012, 30 (7): 693-700. 10.1038/nbt.2280.

-

Lander Eric S, Michael Waterman: Genomic mapping by fingerprinting random clones: a mathematical analysis. Genomics. 1988, 2 (three): 231-239. 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90007-nine.

-

Esko Ukkonen: Approximate string-matching with q-grams and maximal matches. Theoretical reckoner science. 1992, 92 (i): 191-211. ten.1016/0304-3975(92)90143-4.

-

Asif Khalak, Ka Lam, Greg Concepcion, David Tse: Conditions on finishable read sets for automated de novo genome sequencing. Sequencing Finishing and Analysis in the Hereafter. 2013, May

-

Abolfazl Motahari, Kannan Ramchandran, David Tse, Nan Ma: Optimal dna shotgun sequencing. Noisy reads are as adept equally noiseless reads.Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Symposium on Data Theory. 2013, Istanbul,Turkey, July 7-12,2013

-

Giuseppe Narzisi, Bud Mishra: Comparing de novo genome assembly:The long and short of it. PLoS I. 2011, 6 (iv): e19175-10.1371/periodical.pone.0019175. 04

-

Daniel Zerbino, Ewan Birney: Velvet algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de bruijn graphs. Genome enquiry. 2008, eighteen (5): 821-829. ten.1101/gr.074492.107.

-

Sante Gnerre, Iain MacCallum, Dariusz Przybylski, Filipe Ribeiro, Joshua Burton, Bruce Walker, Ted Sharpe, Giles Hall, Terrance Shea, Sean Sykes: High-quality draft assemblies of mammalian genomes from massively parallel sequence data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011, 108 (4): 1513-1518. 10.1073/pnas.1017351108.

-

Jared Simpson, Richard Durbin: Efficient de novo associates of large genomes using compressed information structures. Genome Research. 2012, 22 (3): 549-556. 10.1101/gr.126953.111.

-

Ka-Kit Lam, Asif Khalak, David Tse: [http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/~kakitone]

Acknowledgements

The associates experiments were partly done on the computing infrastructure of Pacific Biosciences.

Declarations

The authors K.Chiliad.L and D.T. are partially supported by the Center for Science of Data (CSoI), an NSF Scientific discipline and Technology Center, under grant agreement CCF-0939370.

This article has been published every bit part of BMC Bioinformatics Volume xv Supplement nine, 2014: Proceedings of the 4th Annual RECOMB Satellite Workshop on Massively Parallel Sequencing (RECOMB-Seq 2014). The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcbioinformatics/supplements/15/S9.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Boosted information

Competing interests

The authors K.K.50 and A.K are or were employees of Pacific Biosciences, a company commercializing Dna sequencing technologies at the time that this work was completed.

Authors' contributions

K.K.50, A.K and D.T performed enquiry and wrote the manuscript. 1000.K.L implemented the algorithms and performed the experiments.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed nether a Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilize, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and bespeak if changes were made.

The images or other tertiary political party material in this article are included in the commodity'due south Artistic Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is non included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended utilise is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you lot will need to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zippo/i.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the information.

Reprints and Permissions

Nigh this article

Cite this article

Lam, KK., Khalak, A. & Tse, D. Near-optimal associates for shotgun sequencing with noisy reads. BMC Bioinformatics 15, S4 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-S9-S4

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-S9-S4

Keywords

- De novo sequence assembly

- genome finishing

- methods for emerging sequencing technologies

Source: https://bmcbioinformatics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2105-15-S9-S4

0 Response to "Optimal Dna Shotgun Sequencing: Noisy Reads Are as Good as Noiseless Reads"

Post a Comment